by Annette Ekin

To avoid climate breakdown, eliminating fossil fuels is the easy part, according to Professor Johan Rockström, co-director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany. He says that safeguarding biological resources such as water, soil and biodiversity will be the ultimate test of whether global warming targets can be reached.

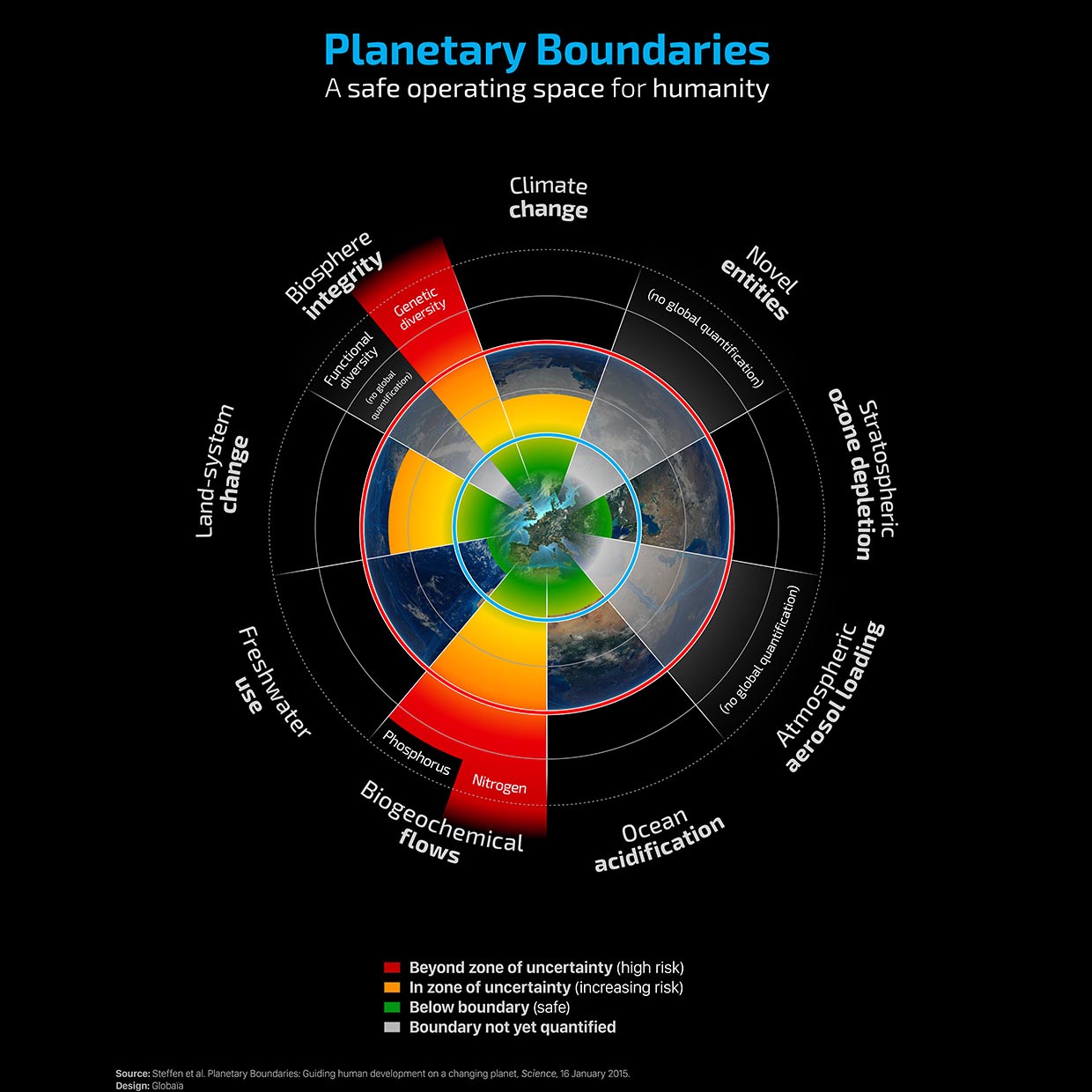

You’ve led the science on the framework of nine so-called planetary boundaries that we shouldn’t cross, which include climate change, but also factors such as land-system change and freshwater use. Why take this approach?

‘(The framework) answers where are the biophysical processes in the Earth’s system that regulate our ability to have a stable climate system and planet. And what you find is that it’s not only about carbon, it’s also about biological systems and processes. It is taking all the planetary boundaries seriously and (recognising that) they all interact with each other.’

How does this approach tie in with the challenge to limit global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, as detailed in the 8 October report from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change?

‘If you read the 1.5°C report carefully, it tells you that, yes, we have to basically decarbonise the world’s energy system by 2045, 2050 by the latest, to stand a chance at 1.5°C. But the assumption is, and it’s really a prerequisite to that feat, that the overall resilience of the planet is maintained, that carbon continues to be sequestered (stored) in all our natural ecosystems.

‘How we deal with natural capital and the living biosphere will be fundamental to whether we will fail or succeed with Paris (the Paris Agreement to limit global warming).’

The EU this month announced its new strategy on the bioeconomy – the part of the economy that deals with natural resources – to bring the bloc closer to the Paris climate objectives. Why is this important?

‘We focus all our attention on coal, oil and natural gas, but when you look at the agenda overall, that’s the easier part of the climate challenge. The much more challenging part is water, soil, biodiversity, nitrogen, phosphorus, the bio dimension of the economy and of the climate challenge.

‘Not only do I see many opportunities in a bio-based resource economy, I also see enormous challenges to get this right.

‘The key here is to take a systems approach (i.e. understand how ecosystems and climate interact) and to take a full life cycle approach, and then to look at the systemic challenges around all the aspects of the bioeconomy. If one does that, I think many solutions will emerge.’

What are some of the important solutions that are emerging?

‘I think one of the obvious low-hanging fruits … is to close the loop on organic waste by closing the loop on nitrogen, phosphorus and carbon. This halts pollution and provides win-win outputs, like biogas generation and new products from waste recycling, basically shifting (away) from our linear process of dealing with all biological resources – particularly in urban environments.

‘It is actually quite a shocking reality that we still operate our European modern societies in a linear way, where nitrogen and phosphorus originate from other continents. (These are) nutrients that we then transport through our imported food in massive trade schemes over to Europe and then we consume them, create waste, treat the waste as well as we can, while large portions of nutrients end up eutrophying (reducing oxygen in) downstream rivers, groundwater and coastal zones, which ultimately leads to sever degradation of coastal ecosystems. That chain has to be broken.

‘(This) has massive synergies because any form of waste recycling of organics gives you additional energy, such as biogas, which is used in many countries in Europe. Strictly speaking, today, biogas is the only truly renewable fuel for mobility.’

Where else do you see potential?

‘The second (solution) is that we must recognise the important potential also in the temperate zone in Europe to develop a diverse portfolio on bioenergy solutions, from heating systems based on biomass pellets from forest industry residuals to production of forest-based liquid fuels. This is debated and also coloured by old perspectives from the environmental movement, saying that anything that has to do with cutting down trees must, by definition, be a threat to conservation.’

And that’s not the case?

‘Unfortunately, we are not recognising the importance and potential of sustainable stewardship of bioresources. We must admit we live in modern societies where every square metre of also natural ecosystems are anthropogenically influenced – there’s no such thing as pristine nature. We need to conserve biodiversity, definitely, and in particular safeguard remaining original forests, but we also need to be active sustainable stewards of our forest capital and (make sure) that in so doing we have biomass sources that we can transform into energy to power both industry and our mobility.’

‘How we deal with natural capital and the living biosphere will be fundamental to whether we will fail or succeed with Paris.’

Prof. Johan Rockström, Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, Germany

Any other solutions?

‘And then third … is to phase out concrete building material and really go big with wood-based infrastructures in societies – from private housing to multi-level buildings. This is the only true biological carbon sink we have because all forms of tree planting are a very uncertain carbon sink as we can abruptly lose all stored carbon in forest fires and disease outbreaks (for example). But if you really invest big time in technology development for wood-based construction you can basically sequester carbon for the next 100 years for each building.’

How can your planetary boundary approach help shape decisions about what actions to take?

‘You can have almost an infinite number of solutions within the safe operating space of planetary boundaries, but they provide you with scientific targets creating the outer fence of your playing field. That, then, can be very reassuring for a nation, or a sector, or a region like the European Union, to say, “Okay, let’s now quantify these planetary boundaries and say that whatever we do in the bioeconomy must operate within these quantitative biophysical boundaries.”’

If we are going to live within planetary boundaries, then presumably we need a way to measure them. Is that possible?

‘Yes it is possible. The first task is to define, through Earth system analysis, where the boundaries are. That’s the task that I, and my scientific peers with me, have focused our attention on. The planet boundary framework is in no way a solution or a monitoring scheme. It gives you the boundaries within which we have a good chance of maintaining a stable planet.

‘Then, of course, the exciting question is, where are we and how are we progressing over time against these boundaries? Now, can we measure that? Yes, we have increasing (measuring) capabilities … based on data from, for example, global Earth observation systems.

‘For example, the Global Carbon Project estimates, each year, how nations and the world are doing against the planet boundary on climate, which, by the way, since 2009 has been set at around 1.3°C (i.e. if the Earth warms any more than this, we have crossed a planetary boundary).’

That’s at a global level but how do you divvy up the boundaries between nations?

‘We are working very hard, as are very many research groups around the world, to develop methodologies of how to quantify the boundaries for different nations and for different sectors and in society. That is a challenge, definitely. It is possible, scientifically, to define, for example, that 10 million tonnes of phosphorous maximum are allowed to flow into the oceans each year. That’s a global boundary number.

‘Now the question is, how do you distribute that between Germany and the US and China in a scientific but also in a transparent and equitable way – i.e. how is the global phosphorus budget to be distributed in quantitative budgets between nations?’

‘We’ve come a long way on climate to (be able to) do this. There are many methodologies of how to share the remaining carbon budget based on historic emissions and levels of economic growth, for example. The European Environment Agency has developed a methodology to adapt the planetary framework for the EU. I am quite optimistic, actually, because we see that countries like Switzerland, Sweden, Germany and New Zealand are, or have expressed interest in, taking the planetary framework and making it operational at the national scale.’

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Originally published on Horizon.