Research suggests that where we live can affect our mental health but Dr MarcoHelbich, an urban geographer at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, believes these studies only offer a limited snapshot of our lives. Using a smartphone app and register data, he is tracking people through their daily routines and their residential history to see whether mental health is affected by where we live, work and socialise. His findings could change how we design our cities.

What do we already know about how the natural and built environment affects rates of depression and suicide?

‘Depression and suicide are influenced by several determinants – a person’s sex, age, lifestyle habits and life events can help to either increase or mitigate the risk. Tentative links between suicide mortality and sunshine, green space, lithium in drinking water, and air pollution have been reported.’

What about the influence of the built environment – is there an urban-rural divide?

‘Researchers have found that the risk of depression and committing suicide varies between cities and the countryside. But the reality is more complex than such an urban-rural divide because the environment varies locally.

‘Our team has shown that living near parks and forests – known as ‘green spaces’– reduces antidepressant prescription rates and your risk of suicide. Most of this – including our own study – is based on aggregate data at a single moment in time. This just gives us a snapshot.

‘What we need now is a detailed study of environmental exposure measures, ideally on an individual level, looking at where, when and for how long people were exposed.’

How else is current research limited?

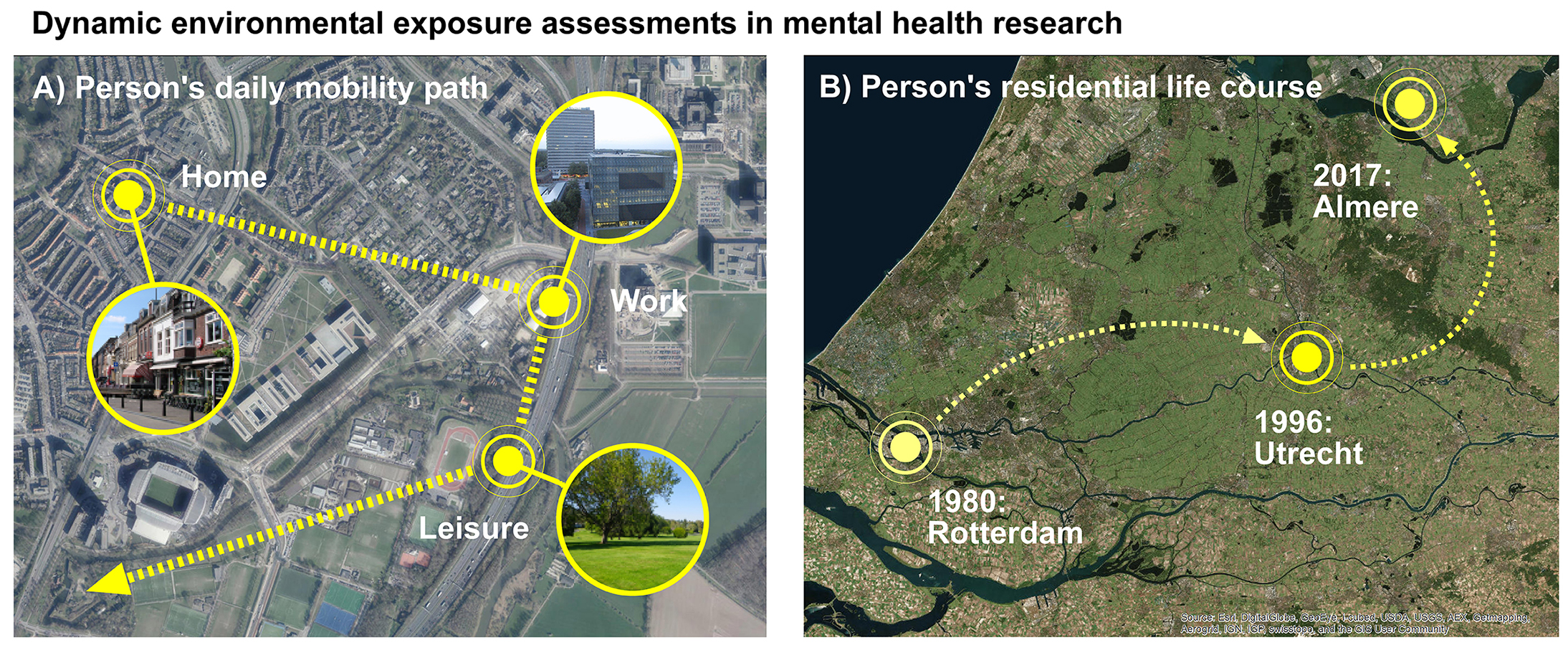

‘Existing knowledge is based on the simplistic assumption that the environment where a person lives is the only relevant source of exposure. In reality, humans continuously interact with the environment throughout the day and over their lifetime. Think about how and where you work, where you do leisure activities, where you meet friends – not all of these are tied to your residential home, they are distributed across multiple locations in a city.

‘For example, you may reside in a calm, green, high social status neighbourhood but during the day you spend most of your time in a dense, noisy, polluted, stressful environment. That’s why using someone’s address as a basis of understanding their environmental exposures is limited.

‘A similar line of thought applies considering residential moves of people. Most people change their residential location over the course of their life a couple of times. Exposures where people lived in the past may still be of relevance for suicide risk later in life.

‘Perhaps someone lives in a leafy suburb with lots of green space today, but has spent their first 20 years in a deprived neighbourhood. They may still be at higher risk of suicide due to their past exposure to risk factors.’

You’re running a project called NEEDS, which is addressing these two issues. What are you looking at?

‘We are focusing on these dynamic exposures over time which we assume to have an impact on people’s vulnerability to mental illness. This will give a clearer picture of how the environment affects depression and suicide mortality. Rather than looking at aggregated data, we are looking at all individuals in the Netherlands over more than 20 years.’

How are you going about that?

‘We are working with Statistics Netherlands to invite 45,000 people to complete an online questionnaire. This will give us information about demographics, socioeconomic backgrounds, and life events that might influence depression. We then invite them to download an app that will collect data through their smartphone for one week.

‘Exposures where people lived in the past may still be of relevance for suicide risk later in life.’

Dr Marco Helbich, Utrecht University, the Netherlands

‘The app uses GPS to reveal mobility patterns: it shows us where they are, what path they took, how often they make and receive phone calls, and their use of social media. This gives us a better understanding of their social network. It is known from the literature that people in regular contact with friends are at lower risk of depression and suicide. Isolation, on the other hand, is an important risk factor for depression.

‘We can then look at geospatial information to examine their proximity to green spaces, rivers, traffic, heavy industry and so on. In addition, registry databases from Statistics Netherlands can provide data on income, sex, age and medication history going back to 1995. We will also trace their residential patterns – we’ll know exactly where they lived 20 years ago.

‘This will give us in-depth knowledge about how exposure duration, exposure sequences, and exposure accumulation across space and over time trigger depression and affect suicide risk later in life. This is much more individualised than any previous work and promises to provide us with a very rich dataset.’

When will you have results?

‘About 8,000 people participated in the survey and more than 500 people are currently using the app and this will rise as we continue to recruit until November. Then we will develop statistical and machine learning models required to analyse the data that we have collected. The NEEDS project runs until 2023 and we hope to publish our findings before then and to engage with academics and decision-makers about how to apply our results.’

What impact could your work have?

‘If we prove direct cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between depression, suicide and the environment – such as green spaces, for example – then it increases the need for policymakers to take action. Policymakers and urban planners will need to come up with strategies that support people’s mental health.

‘We aim to deliver recommendations to support society as a whole and improve people’s health. Urban planners have a key role because neighbourhoods could be designed to positively affect people’s mental health. Strategies can include, but are not limited to, providing accessible green spaces, urban design that supports incoming sunlight, and measures to encourage walking and cycling while reducing car-based emissions.’

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Originally published on Horizon.