Workshops focusing on intergroup emotions are showing how deeply-rooted beliefs can be changed to support conflict resolution.

Group interventions, each lasting just five hours, broadened dozens of Israelis’ views on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, a study published in January showed. The study explored how in unyielding conflicts, the belief that one group can change their views motivates the other to make concessions to overcome enmity.

For more than a decade, Professor Eran Halperin, an author of the study and a psychologist at the Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya near Tel Aviv, Israel, has investigated how emotions shared by entire communities influence politics and intergroup conflicts. As part of his on-going Emotions in Conflict project, Prof. Halperin is conducting psychology-based interventions to dismantle social prejudices, hatred and promote people’s support for the Israeli-Palestinian peace process.

‘Hatred arises from the conviction that others cannot change, that they act in a hurtful or violent manner because it is in their nature,’ said Prof. Halperin. ‘When Israelis think that Palestinians can change, they can’t really hate them anymore.’

For the study published in January, researchers recruited 508 Jewish Israelis to take part in workshops in Haifa, Beer-Sheva and Herzliya in Israel. The workshops grouped participants in classes of 12 to 20 and presented them with lectures and slideshows containing historical evidence of how communities elsewhere in the world have changed their views on major issues such as racial segregation in the United States or even public attitudes towards smoking. Between lessons, participants were invited to reflect on changes in group mindsets that they had witnessed over their lifetime.

‘Hatred arises from the conviction that others cannot change, that they act in a hurtful or violent manner because it is in their nature.’

– Professor Eran Halperin at the Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya near Tel Aviv, Israel

A key trick to the training sessions was to mask their true objective. Participants knew nothing about the social implications of Prof. Halperin’s work — instead, they thought they were taking part in a study about improving leadership training techniques. This distance was designed to let the subjects approach an emotional topic without bias, take in new information and reconcile it with ingrained feelings in their own time.

Prof. Halperin says that one in five participants reported feeling more hopeful about resolving the conflict and more willing to make concessions towards Palestinians to work towards peace.

‘A society without hope has very few chances of advancing towards a peace process,’ said Prof. Halperin. Such interventions can reshape people’s emotions and behaviour, he says.

Prof. Halperin’s study showed that other psychological interventions, such as trying to understand the other side’s perspective to empathise with them, can also reduce feelings leading to sectarian divisions, but their impact tends to fade over time. In contrast, focusing on a group’s ability to change is a more effective way of reducing feelings of anger and hatred over longer periods, according to the study. ‘It is like giving people a new prism though which to see the world,’ said Prof. Halperin. Many participants even reported views that grew more tolerant over the six months following the intervention.

Prof. Halperin says the technique might help ease social tensions in other contexts as well, but he urges caution, saying that one notable issue is that people are generally reticent when self-reporting emotions and political views. People are unusually frank when it comes to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, according to Prof. Halperin.

‘People usually don’t like to admit that they are afraid, and they definitely don’t like to say that they hate someone,’ he said. ‘When we study emotions in other contexts (in the US, for instance) we try to use implicit or physiological measures of emotion because the direct measures are simply irrelevant.’

Reading faces

Research conducted by Dr Bert Bakker at the University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands is exploring such measures.

Dr Bakker is studying what physiological responses say about the human emotions causing them. He says that the intensity of emotions, whether enjoyable or not, tends to scale with how much our fingers sweat. Cheek muscles responsible for smiling can suggest positive reactions, descending eyebrows signal negative ones, and a certain twitch of the nose usually expresses disgust.

Psychologists already use some of these cues to help patients work through chronic anxieties and to add to the evidence produced by lie detectors. Dr Bakker is among the first to use physiological responses to find out whether emotions influence political convictions.

‘We have seen massive changes in recent years with political conflict emerging across Western Europe and the United States,’ said Dr Bakker. He says that political commentators have speculated on the role of emotions in polarising voter sentiment, but so far, the only insight they have are self-reported survey questions. By tracking the physiological responses of test participants, he hopes to test complementary ways of surveying political emotions.

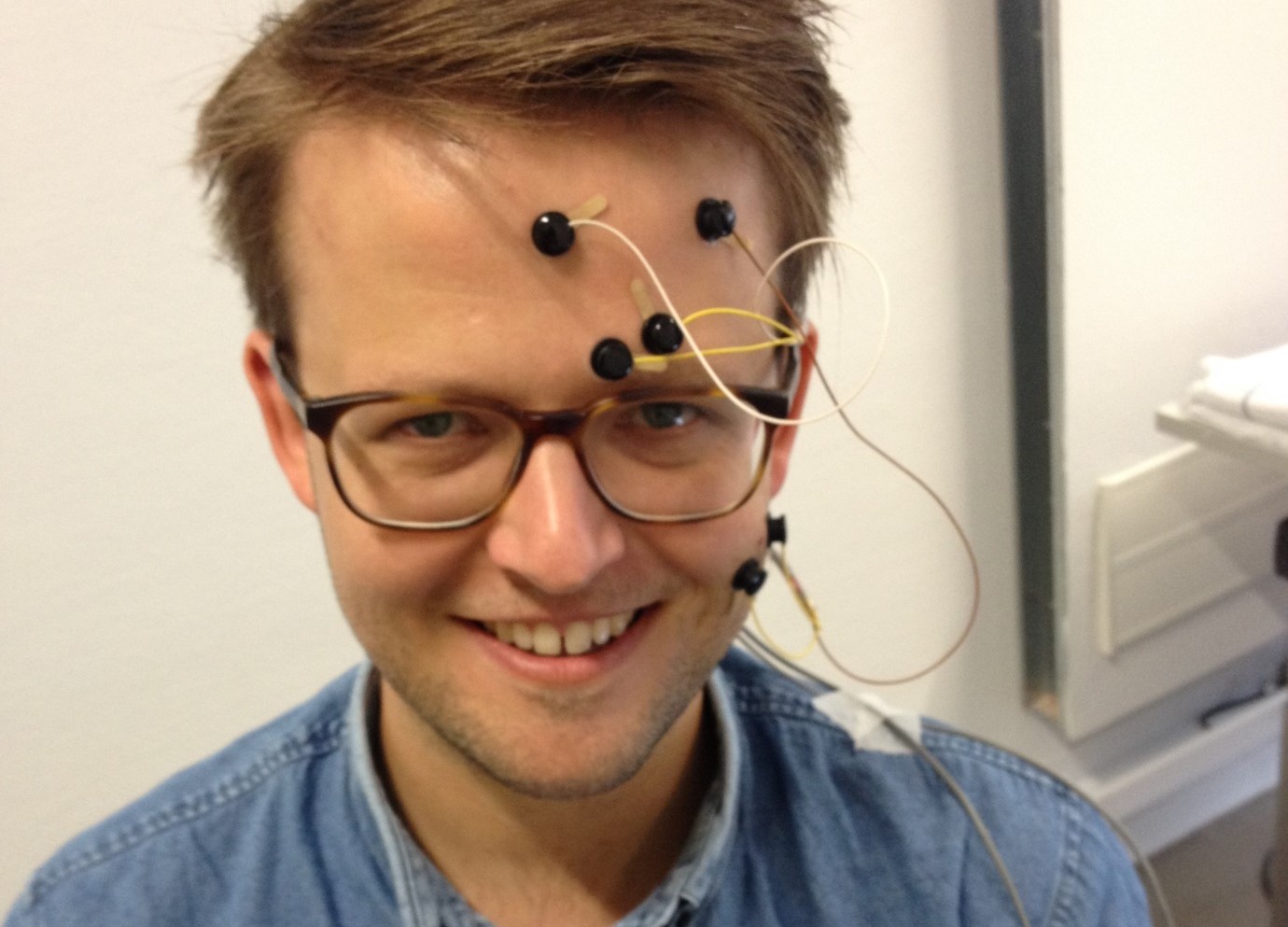

Dr Bakker crossed the Atlantic last year to study the charged arena of American politics as part of the HotPolitics project. Along with partners at Temple University in Philadelphia, US, he attached electrodes to the face and fingertips of more than 200 volunteers. These participants viewed images and sentences relating to abortion, taxes, Donald Trump and other polarising topics. When participants were asked to fill in questionnaires on how each politically loaded message made them feel, researchers tracked their physiological reaction in real time.

‘In previous research, we found that survey answers and physiological responses don’t always match,’ said Dr Bakker. For instance, study participants sometimes self-reported feeling angry about immigration while their bodies showed no discernible emotion, or vice versa. To investigate the disparity, Dr Bakker incorporated messages into his study that are likely to cause physiological responses of anxiety or revulsion but that are politically neutral — such as pictures of spiders.

Over the coming months, he will compare the reactions to neutral images with those relating to political polemics.

The results could shed light on whether participants truthfully self-report their political emotions and also, what their emotional responses — or lack thereof — reveal about how strongly they feel about political issues.

Over the coming year, Dr Bakker will perform physiological measurements in the Netherlands to explore whether emotions play a key role in the political divisions emerging across Western democracies.

‘The political climate is very different between the Netherlands and the United States,’ he said, ‘but there is no reason to expect that people’s sweat glands behave differently.’

The research in this article was funded by the EU. If you liked this article, please consider sharing it on social media.

Originally published at horizon-magazine.eu.