How people and deliveries get to their final destination is currently making urban environments harder places to live, and cities need to solve this ‘last mile problem’ by using a combination of ‘carrot and stick’ measures, according to Karen Vancluysen, secretary general of Polis, a network of European cities and regions working on sustainable innovative transport solutions.

What exactly is the last mile problem and how does the challenge differ between freight deliveries and personal journeys?

‘When we talk about the last mile, we refer to the final leg of a journey, from a transportation hub to a final destination. This applies both to the movement of people and of goods.

‘When we talk about the last mile in urban freight, it’s basically finding a way to mitigate the negative (environmental) impacts of this transport. That means, for example, using vehicles which are more adapted to the urban environment, not huge trucks that get into our city centres.

‘Then there is the last mile and passenger transport. If we want citizens to leave their cars behind and use public transport, we have to make sure we also take this aspect into account. And this is something that’s become quite a hot topic lately (with) all these new mobility services popping up in our cities, the scooters and (shared) bikes – basically micro mobility. What they claim is that they offer a solution for the last urban mile, but ideally, you just walk because that’s the cleanest mode of transport, or just take your bike. Although it’s always good to extend the range of solutions available.’

‘Measures that are good for air quality and for reducing congestion are usually also benefiting decarbonisation.’

Karen Vancluysen, Secretary General, Polis

Why do we need to solve the last mile problem?

‘Air pollution (from combustion engines) is a very severe problem. Citizens (and others) have taken cities to court because they’re not meeting the air quality targets that have been set on the European level. We also see that (the number of crashes involving) vulnerable road users in the urban environment are not going down at the pace that we would like to see. And then there is the dimension of congestion: our cities are blocked, we have endless traffic jams that we need to address to make sure that it’s still nice to live in a city and that the quality of life is protected.’

‘The good news is that measures that are good for air quality and for reducing congestion are usually also benefiting decarbonisation.’

How do we address these challenges?

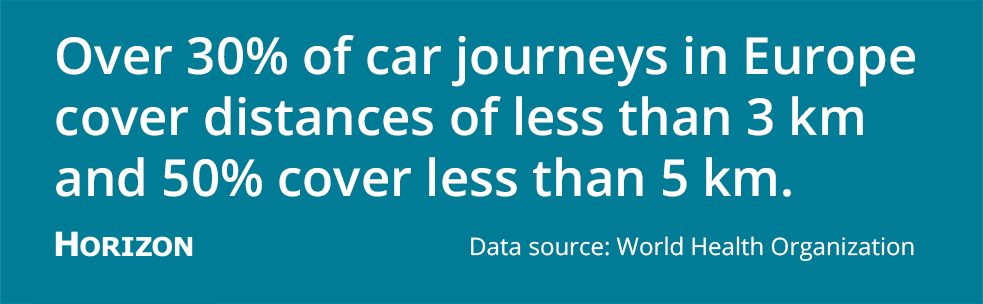

‘Modal shift is the magic word – moving away from (private) car use (in city centres) to the benefit of more public transport, more cycling, more walking, complemented with these new emerging modes like micro (and shared) mobility.

‘We shouldn’t forget that the backbone of any urban transport system should be high quality public transport, as well as cycling and walking. The last urban mile is talked (about) a lot, but actually, in many cases, it can really be beaten by walking. And we will always need public transport to move large groups of people in a very efficient and clean way.

‘(But) it’s always good to extend the range of solutions available. So, we (Polis) have been engaging with the micro mobility sector, which is essentially private-sector driven. We’re looking at how we can introduce these new mobility services in the urban mobility ecosystem in a way that also helps address (local) needs. Importantly, we have to be aware that if we don’t regulate or frame these services properly, we could end up in a situation where the modal shift they bring about is not the (one) cities are looking for (e.g. replacing walking or public transport trips rather than car trips).

‘Take automated cars for example, another innovation and disruption that is coming our way. If (cities) don’t set the rules of the game, they could lead to more kilometres driven, it could lead to urban sprawl and more congestion. Automation in cities should therefore be looked at in an electrified and shared scenario.’

It sounds as though a lot of the solutions already exist. How do we put them into practice?

‘We need both carrots and sticks. We need political leadership, we need cities that have the courage to take measures which might be unpopular (with citizens) at first – urban vehicle access regulations, for example. So, restricting access to city centres (for cars), whether it’s through low emission zones, congestion charges (or other pricing measures).

‘Then you have trends like mobility as a service. But (just) because you offer people an app where they have an integrated package of mobility services (doesn’t mean) that they (will) easily use it and automatically switch to a more sustainable mobility behaviour. Again, this would have to be accompanied by other measures.

‘We might also move to a situation where we need to explore new business models, new types of public-private partnerships. If we want to see a meaningful role for these new mobility services, then (cities) might have to subsidise them partly. Currently, all these micro mobility services are living off their venture capital, but at some point, they will need to start generating income and making money, and already the services are quite expensive today for the user.’

It seems solving the last mile problem would combine several new and existing modes of transport while being operated by both public and private sectors – how do you manage such a complicated network?

‘That’s where we see a leading role for cities. They should set the rules of the game and decide in what way they allow these innovative services to thrive. That’s what we see happening at the moment with micro mobility – that cities are developing regulatory frameworks. We have to see what works best, which regulations are positive both for the city and for the operators.

‘(Polis) is involved in a number of European funded projects with our member cities and regions which act as testbeds for the innovations that are coming from research and industry. When it comes to urban freight, we are currently involved in a project (ASSURED) that is looking at fast-charging solutions for trucks and buses, for example. So that’s looking at electrification, cleaning up public transport, as well as finding cleaner solutions for urban freight.

‘Within the context of urban (passenger) mobility, there have been very useful projects such as the Flow Project, for example, which upgraded traffic models in such a way that walking and cycling were put on an equal footing with other transport modes. It was about providing cities with a traffic modelling tool that could help them quantify the impact of certain measures in favour of cycling and walking.’

Cities need to set the rules of the game when it comes to innovative mobility services such as e-scooters and shared bikes, says Karen Vancluysen. Image credit – Polis network

Is there a risk that some members of society could get left behind by changing the way we get around?

‘We have to be aware that there are still people with no access to a mobile phone or to internet and provide alternatives (for them to access new services). At the same time, these new mobility services also open up a lot of new possibilities to offer services that are targeted to specific needs that cannot be met by mass transit. There’s a great opportunity to make the transport system more inclusive by capitalising on the new services coming to the market.

‘Striking the right balance between addressing climate challenges and offering inclusive services where no one is left behind will be an important priority in the coming years.’

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

The research in this article was funded by the EU. If you liked this article, please consider sharing it on social media.