by Ethan Bilby

It may be that life is lurking out there on other planets. But stuck here on Earth, how can we ever know for sure? A good place to start is by looking for the compounds on other worlds that are known to be the key ingredients of life as we know it.

Detecting these so-called biosignatures, compounds that are known to be produced by living organisms, would be strong evidence that worlds may contain life. But picking up chemicals from such distant worlds, and choosing the right compounds to look for, is complicated.

Professor Ignas Snellen at Leiden University in the Netherlands has been refining techniques that combine data from the largest ground-based telescopes with high-contrast imaging that can reveal faint objects like planets. The telescopes use high-precision spectroscopy to examine the different wavelengths of the light they detect from space.

‘You want to filter out the actual starlight as much as possible to make visible whatever information you can get from the exoplanet,’ Prof. Snellen said.

By examining the starlight that filters through a planet’s atmosphere and reaches us on Earth, it’s possible to derive the types of gases that are present.

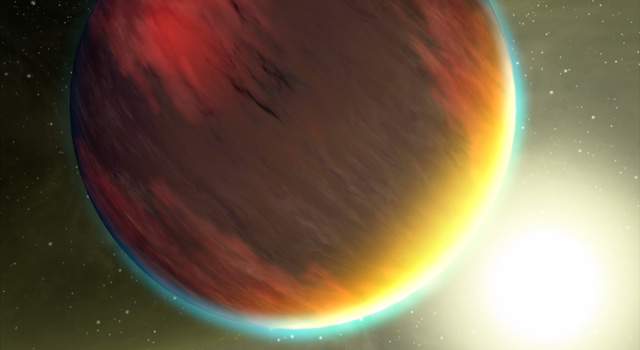

While telescopes are not yet large enough to examine the spectra for Earth-size planets, scientists are honing their methods on larger exoplanets, so-called hot Jupiters, which are far too hot to support life as we know it. These are gas giant exoplanets that orbit very closely to their parent star. So closely, in fact, that they are tidally locked, like our moon, with the exoplanet rotating only once with every orbit around its star.

With one side of such planets always in light and the other always in darkness, the light side gets so hot that the atmosphere can boil off, creating a wind of matter flowing off the planet, a bit like a comet’s tail.

In the EXOPLANETBIO project, Prof. Snellen and his team used high-precision spectroscopy for the first time to confirm the amount of helium in a hot Jupiter’s atmosphere using ground-based telescopes, which can reveal how far gone this process is.

‘That was a breakthrough for these hot Jupiters,’ he said. ‘These kinds of exospheric tails were known, but they are very difficult to observe because the only way to see them was through detecting hydrogen, which can’t be detected through Earth’s atmosphere, using the Hubble space telescope.

‘Now, with the stronger helium line we can do this very well from the ground with telescopes.’

Understanding if a hot Jupiter may bleed off its atmosphere, and how long it may take, can explain how the atmospheres of all exoplanets change over time.

‘These kind of atmospheric escape processes are not very important now, but in the early solar system they were, because the sun was a lot more active,’ Prof. Snellen said.

Exoplanet climate

Using these new techniques, his team has also been able to achieve another first, detecting the spin rate – how fast a planet rotates – and orbital velocity of exoplanets.

‘The spin rates on hot Jupiters are generally quite low, as they are generally tidally locked,’ he said.

That can reveal something about the climate and related weather on the exoplanet.

‘When a planet rotates fast, it gets bands like Jupiter. The Earth rotates slower and has some bands, but it’s still mostly dominated by low pressure systems. Now, if you have a hot Jupiter which is rotating even slower, you wouldn’t get any banded structure. You get very different weather systems,’ he said.

He has been able to observe winds high up in the atmosphere of such planets, as energy from the hotter, eternal-day side is rotated to the cooler night side.

Prof. Snellen is confident that an upgrade to the CRIRES (CRyogenic high-resolution InfraRed Echelle Spectrograph) instrument, set to go online next year on the European Southern Observatory’s (ESO) Very Large Telescope, will let them find compounds such as methane on cooler planets. Methane can be a component in life if it is found in Earth-size planets.

‘I see this as a kind of a playing ground. We are learning the methods now that we can someday apply to Earth-like planets. The (ESO’s) Extremely Large Telescope should be ready in 2026, and with that we can start to probe Earth-like planets.’

Sign of life

Yet even if you have good samples from rocky, Earth-size planets, how do you know if a compound is truly a sign of life?

‘Geology is very good at producing things that look like life, such as methane. It could come from cows or it could come from rocks,’ said Professor Kevin Heng, a professor at the University of Bern in Switzerland.

‘If you think about biosignatures, they have to satisfy various conditions. They have to not be mimicked by geology, they have to exist in the atmosphere for long periods of time, meaning that they are very stable or are replenished somehow, and they have to be detectable.’

As part of the EXOKLEIN project, Prof. Heng is working on determining if such compounds, like methyl chloride and ammonia, can last long enough in exoplanetary atmospheres to study, by modelling small planets around dwarf stars. It’s a particular challenge for Earth-size planets, whose atmospheres can change over time.

‘Geology is very good at producing things that look like life, such as methane. It could come from cows or it could come from rocks.’

Dr Kevin Heng, University of Bern, Switzerland

‘If you look at a planet like Jupiter … they kind of look like the sun. They are made of hydrogen, they have trace elements of metals and so on. Based on differences between the planet and the star I can figure out how it formed. It would keep a fossil record of how it formed,’ Prof. Heng said.

But for smaller planets, their atmospheres have changed significantly over time through processes like the carbon cycle.

‘We spent the last eight to 10 years figuring out how to use climate models designed for Earth (on exoplanets), and how to tweak and modify them.’

Those models will be used to provide potential explanations for data collected when instruments are capable of surveying smaller planets for life, to understand if compounds are really biosignatures or can be explained away as geological.

‘Extraordinary claims require extraordinary standards of proof, so if something is consistent with not requiring biology, I would say there’s no biology,’ said Prof. Heng.

He is also modelling planets that may have had more dramatic fates. For small planets around red stars to support life, they would need to have a very tight orbit, making them tidally locked like hot Jupiters.

‘This means that the night side is really cold, and maybe cold enough that the gases in the atmosphere would condense into ice. So, you get a runaway condensation and you have no atmosphere – atmospheric collapse,’ he said. Such collapse would leave planets cold and lifeless, like Mars.

While the work is just theoretical now, upcoming missions like the European Space Agency’s CHEOPS satellite and NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope should yield data that he can match up against his theories.

‘When Webb launches (in 2021), there is going to be a quantum leap in the quality of data. It may so happen that atmospheric collapse is so prevalent that half the small planets around red stars don’t have atmospheres.’

The research in this article was funded by the EU’s European Research Council. If you liked this article, please consider sharing it on social media.