As our world becomes more digitalised and connected, we can actually make a virtual copy of it. And such replicas are now being used to improve real world scenarios, from making aircraft production more accurate to preventing oil spills.

A digital twin is a virtual replica of a real life entity, such as a city or a factory, which often evolves in real-time along with its physical counterpart through data gathered through sensors. It can be used as a testing ground to simulate what happens under certain circumstances or provide alerts of potential problems thanks to predictive algorithms.

A virtual replica of a city might, for example, use all kinds of data sources, from city sensors to meteorological data, to simulate a city’s transport system. A simulation could then analyse the effect on air pollution of making a specific zone car-free.

‘A digital twin is a concept that describes many things,’ said Thomas Leurent, CEO and co-founder of Akselos, a Swiss company that builds digital twins for the energy sector. ‘It can be a 3D image that automatically reflects a physical object (for high-precision manufacturing), but it can also be a model that predicts when maintenance of an oil platform needs to take place.’

Using sensors to measure, for example, the strains of structures or wind loads, companies like Akselos make a digital, often real-time, simulation of the physical world. The idea of digital twins, which first emerged in 2002, has its roots in the pairing technology pioneered by NASA who deployed mirrored systems to help rescue Apollo 13. Today, virtual replicas have myriad uses.

Smart city programmes in places such as Portland, the US, for example, use digital twins to model traffic flows, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, is building one of its port to increasingly automate its operations, and attempts have been made to make a virtual copy of the human body for medical purposes.

Wing construction

They are also being used to improve production in the aircraft assembly line. This is the aim of VADIS, a project being carried out by the University of Nottingham and aerospace company Electroimpact, both in the UK.

‘We want to improve quality and reduce assembly time for wing construction,’ said Dr Joseph Griffin, senior aerospace engineer at the University of Nottingham and project manager of VADIS. ‘We want to measure the holes that need to be drilled in a wing skin, and use those measures to update a digital model. This way we can adjust the construction process to a specific component.’

Although many aircraft may look state-of-the-art, some production processes are still old-fashioned and done manually because of lack of digitalisation in the industry, which, in turn, can leave room for error. In wing production, for example, holes may not align exactly as they should, which then requires last-minute adjustments on the assembly line, leading to loss of time.

To address this, VADIS is constructing a frame in which the aircraft skins can be scanned by sensors. This will then be used to create a digital model or twin of the wing, with all its surfaces and holes registered in the smallest detail. This model would then be used to build the corresponding parts so that they align seamlessly for that specific wing.

‘Our new system will mean that components can be manufactured very precisely off-site, and the operators only need to worry about assembly,’ said Dr Griffin. ‘They don’t have to worry about re-drilling and re-working at the last minute.’ In this way operators’ work becomes a lot easier, he says.

VADIS aims to be able to replicate a digital wing skin of up to 10 metres long, with an accuracy of 0.06 millimetres, according to Dr Griffin. ‘(By doing this) we are keeping aircraft production up-to-date and digitalising it,’ Dr Griffin said.

‘We want to improve quality and reduce assembly time for wing construction.’

Dr Joseph Griffin, University of Nottingham, UK

Model

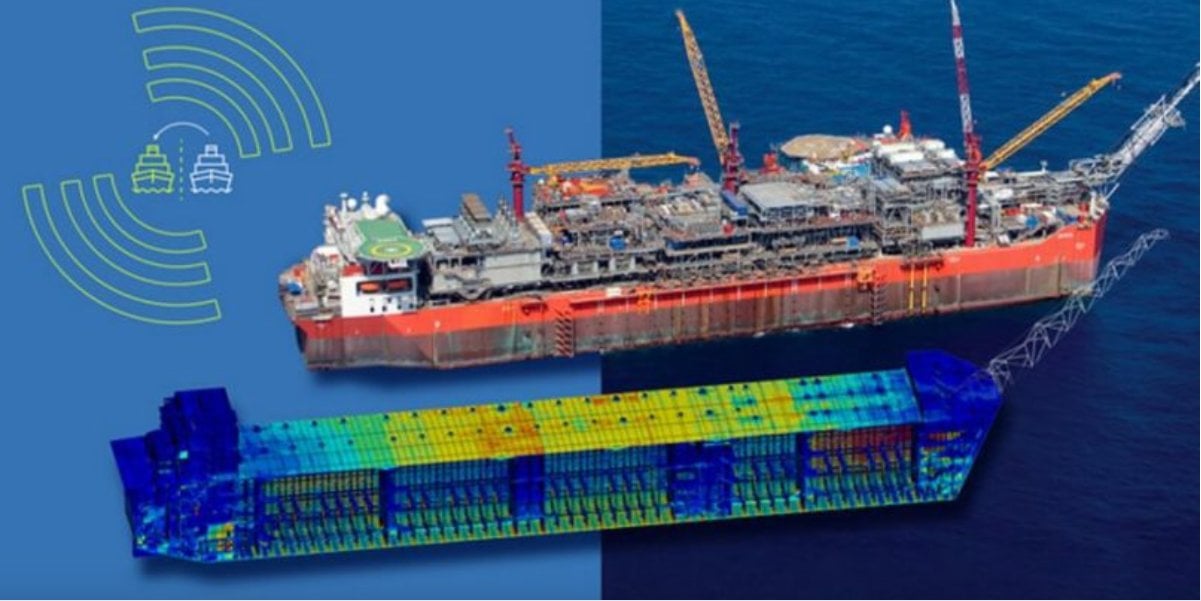

Akselos also uses digital twins to improve maintenance of energy infrastructure. The company’s technology, commercialised through the Akselos Integra Software, models physics of large-scale energy infrastructure and calibrates the models through all kinds of sensors. ‘We model everything from the blades of wind turbines, to (floating) oil (and gas) platforms that are the size of (several) aircraft carriers,’ said Leurent.

They might use a robot to inspect the hull of a floating production storage and offloading (FPSO) unit for oil or gas, attach accelerometers to wind turbine blades or measure the height of waves bashing against the metal of an offshore installation using sensors. All of that data then goes into their model, which simulates the physics of the piece of infrastructure and predicts which parts are the most vulnerable and prone to failure. This in turn allows energy companies to more effectively send out maintenance crews.

‘The traditional approach is to have scheduled maintenance,’ said Leurent. ‘Which yields a huge percentage of what we call false positives. So a maintenance crew is told to inspect an area, but there is nothing for them to do there. This is hardly efficient, because you misdirect your crews (who in turn lose time), and you might miss problems because you cannot look everywhere.’

Of course you can also statistically predict errors based on previous data. But these models are, ‘very coarse’, according to Leurent: they require a lot of data, and still yield high numbers of false positives, particularly for very large objects like FSPOs.

By instead making highly detailed digital replicas, Akselos uses complex models that show companies in real-time where they need to send their maintenance crews.

‘This is highly important,’ said Leurent. ‘Because if you catch a problem early, that’s good. But if you’re late, you might have a very expensive (repair or) oil spill on your hands.’

The research in this article was funded by the EU. If you liked this article, please consider sharing it on social media.

Originally published on Horizon.