by Jonathan O’Callaghan

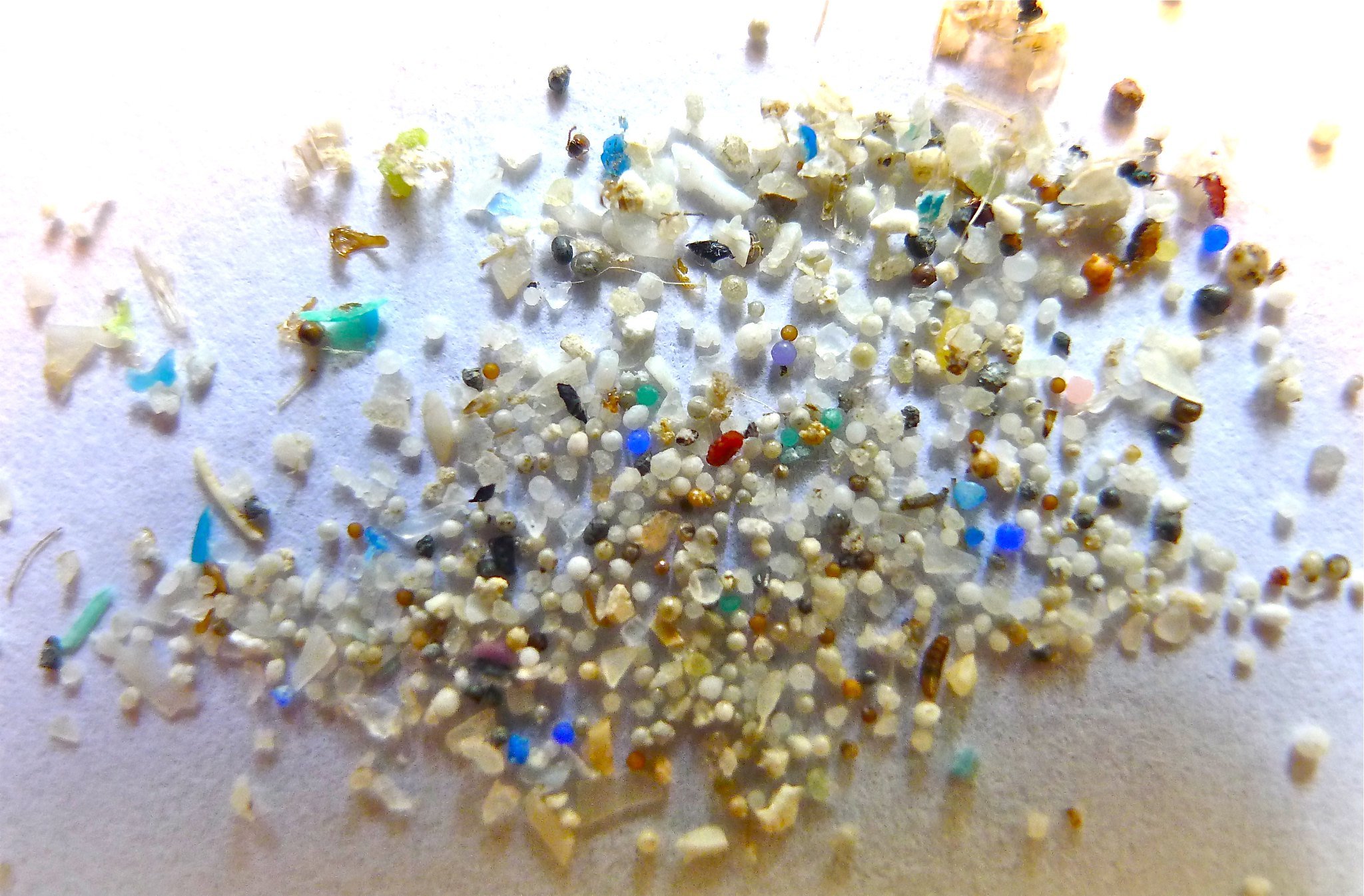

An estimated 5.25 trillion particles of plastic float in Earth’s oceans, threatening not only the health of marine ecosystems and animals, but that of humans in the water we drink and the food we eat. However, research into the extent of the dangers posed by microplastics is still just in its infancy.

On 30 April, the European Commission’s chief scientific advisors released its scientific view on the environmental and health risks of microplastics. The opinion says this pollution could present a significant problem if it goes unchecked and public concern is growing, yet we simply don’t have enough scientific evidence to understand the widespread risks.

To find out the extent of the problem, what we know so far and what needs to be done, Horizon spoke to water expert Professor Bart Koelmans from Wageningen University and Research in the Netherlands. He is chair of the Science Advice for Policy by European Academies (SAPEA) working group, which reviewed the scientific evidence for the new report.

How bad is the microplastics situation today?

‘If you just look at the facts that we know, microplastics are detected in many (places) all over the world, including biota, water, soil and the air. From an aesthetical or ethical reasoning, people would say, “Well, we think it just doesn’t belong there,” then you could say it is already bad. However, others might say it’s more important to first look at the real ecological risks, or human health risks. Then there is just a lot that we do not know. The topic is surrounded by large uncertainty.’

What risk do microplastics pose to our health?

‘There are just a handful of studies that report that there is microplastic in drinking water. There is some microplastic detected in some components of our diet, but it’s so little that you would like to see these studies (about the presence of microplastics) repeated by other groups to make them more rigorous and then reliable. But we know that, of course, there are also microplastics in the diet, so people are exposed to microplastics. However, just the presence of these particles in our environment, or in our food, does not necessarily imply a risk.

‘For smaller plastic, like nanoplastic (less than 0.05mm wide), we know even less. We do not know what the exposure concentrations are and we know very little about the effects. However, we do know that very small particles of other materials, like asbestos, or very small particles that negatively affect air quality can have negative effects on human health when inhaled for longer times (at) higher concentrations.’

What does the new scientific opinion say about the risks?

‘We concluded that we did not see evidence for widespread risk at this moment. (But) we also saw that if nothing would happen (and trends continue), then it is not unlikely that the chances of a risk would increase somewhere in the future. And that somewhere would be like 50 years or 100 years.’

How widespread are microplastics in the world’s water supplies?

‘Very often it’s a couple of particles per litre or even a couple of particles per cubic metre, which is rather low if you consider that organisms are used to living in an environment where particles are present.’

What are the issues with regards to nanoplastics?

‘The issue with nanoplastic is that it’s very small. And the hypothesis then is that because of its small size, it would be able to pass membranes, and therefore cells. So microplastic, which is bigger, for the most part would enter the gut of an organism and leave it, nanoplastics might pass membranes (and remain).’

Would you say that public concern over microplastics surpasses what we actually know about them?

‘I agree with the concern. However, I do not always agree with the reasoning that supports the concern. I think that in the messages with the public or in the media, some of the nuances are lost (due to the simplification of issues).’

Is there enough evidence at the moment to support taking action on microplastics?

‘Yes, because lack of evidence also can support policy. We do not have solid data on what concentrations in the future will be, but if we do an educated guess, using models and data to try to predict whether, for instance, the concentrations of microplastics or nanoplastics in the environment will increase over the decades or decrease, then the answer is quite clear. It will not decrease, it will increase.’

What needs to happen to tackle this issue?

‘There is no silver bullet solution, the one solution that you can summarise in a couple of sentences and that’s it. I think the solution has to come from a combination of things. Are there alternatives for some of the plastics that we use so that we can use less? Can there be other materials that can be used in products, so that there will be less plastics? Can we replace some of the polymers by other polymers that would cause less effects? And then how do we do this? So then there’s the role for policy to stimulate this.’

How long do we have to address the issue of microplastics?

‘I think it just should start now. There is a lot of attention for it now, there are some budgets made available for research, there’s a lot of movement towards the things I just mentioned. You see many groups and stakeholder groups becoming aware of it and starting to move to change. So I think that’s a good thing.

‘The first widespread effect that you could expect from microplastic would be decades, maybe 50 years or 100 years.

‘The good news about plastic is that it can be reversed. I think it is feasible to strongly reduce leakage to the environment, to such an extent that these risks are minor or absent or negligible. There is no widespread risk now and at least we can do something to make it so it will not become a widespread risk in the next decades.’

The research in this article was funded by the EU. If you liked this article, please consider sharing it on social media.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Originally published by Horizon