Scientists in the Middle East are putting politics aside and using the region’s new particle accelerator, SESAME, to collaborate on experiments such as distinguishing between benign and malignant cancer tissues, and analysing historical parchments from religious texts, according to Dr Gihan Kamel, the infrared beamline scientist at the facility.

She will be speaking at a session on science diplomacy at the World Science Forum in Jordan on 10 November with Carlos Moedas, the European Commissioner for Research, Science and Innovation.

Can you tell us a bit about the synchrotron – what is it and how does it work?

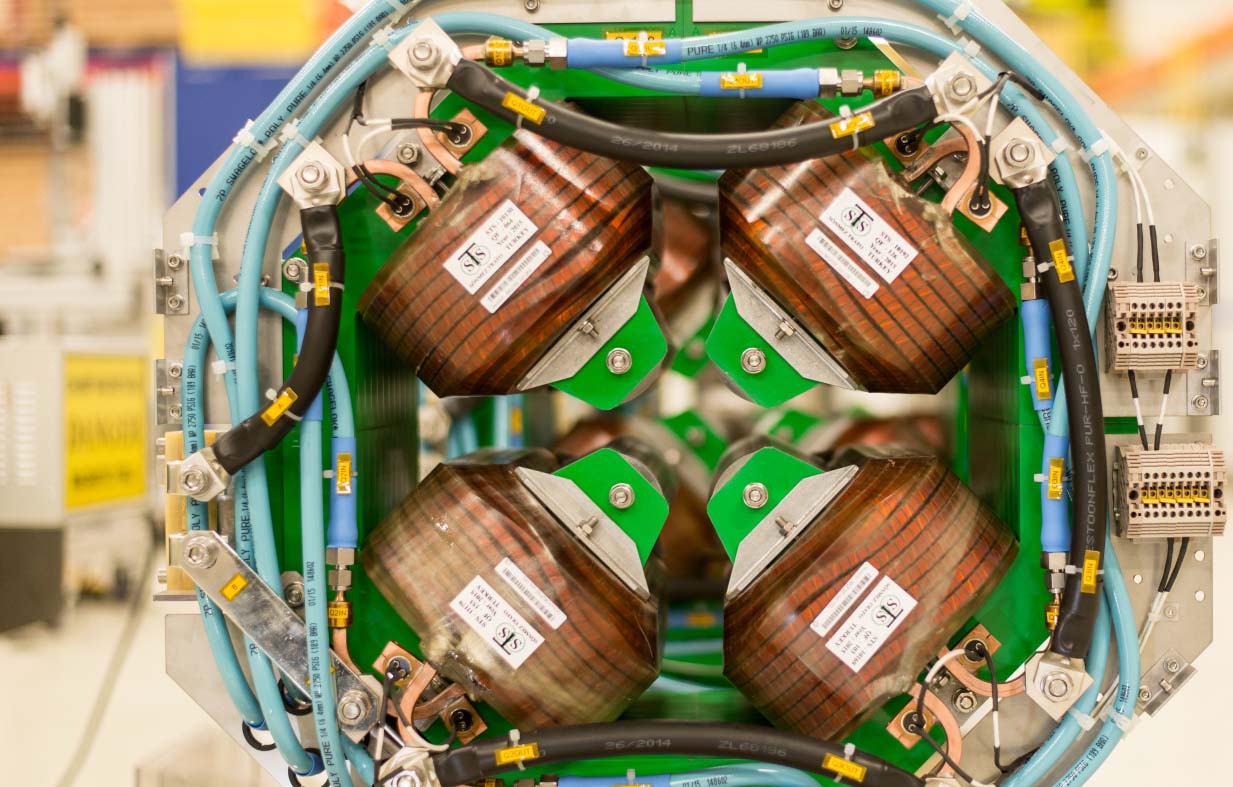

‘Basically, it is considered something like a super-microscope. The basic principle of the synchrotron is to accelerate electrons up to high energy, then we collect a part of the electromagnetic radiation (as) infrared and X-rays. You can perform different experiments or applications that almost are impossible to perform by conventional X-ray or infrared sources because the synchrotron radiation has unique properties – essentially its brightness and resolution. So we can see with the synchrotron what we can never see with any conventional source.

‘SESAME is ramping up towards the operation of two beamlines to take place by the end of 2017.’

The first synchrotron beam at SESAME was recorded earlier this year but in the meantime you’ve been using a very powerful infrared microscope to conduct experiments. Can you tell us about these?

‘(Some of the) experiments that have been conducted there (are) biomedicine – I have an experiment with a user from Pakistan and she worked on using infrared microspectroscopy to distinguish between benign and malignant breast cancer tissues. I had an experiment with another user from Cyprus – she is an archaeologist – doing experiments on ancient human remains dating back to 4 000 years old. Another experiment is with a Jordanian user – she’s analysing historical fragments from Petra, the archaeological site here in Jordan. Other experiments are environmental, investigating (soil and water) from the Palestinian Authority.

‘I also have a collaboration with an Egyptian user on characterisation of historical manuscripts and another experiment with an Iranian user also working on historical parchments from the Koran and the Torah. The applications are really huge and I keep jumping from biomedicine to cultural heritage. Basically, the infrared technique allows us to accept all types of materials, so we jump between all these applications.’

‘We are scientists but we are still humans and we cannot close our eyes or ears to what’s happening around us.’

Dr Gihan Kamel, SESAME

How does SESAME fit into the scientific culture of the region?

‘This year (in) December (will be) our 15th users’ meeting. In the beginning, it was difficult to understand our needs as researchers from one region because of the differences between our countries. Later on, and one users’ meeting after another, it became clear that we have common needs and common requirements, so we are trying to explore as much as we can.

‘So, for me and the beamline, I don’t want always to focus on biomedicine. It’s true that we have common diseases in the Middle East, common biomedical and environmental issues. But also the Middle East is very rich when it comes to archaeology and cultural heritage, and, people come together and when they need to they talk to each other and they find common ways to collaborate. So, for example, this researcher from Cyprus working on ancient human remains, these remains were collected from east Iran.

‘We have to invest in these common links between our researchers. I think an establishment of a synchrotron facility in the Middle East is now becoming maybe the only way to bring people together.’

Do you mean that the only common ground that people with political differences have is their work with the synchrotron because it’s such a complicated machine they have to leave everything outside to work there?

‘Exactly. It’s obvious that a facility like a synchrotron light source takes millions of dollars and also huge expertise and manpower, and it’s also clear that no single country in the Middle East or any developing country is able to have its own synchrotron facility like we see in Europe or the US. SESAME is the only synchrotron facility where all these members are contributing to have it operational.

‘We are starting with scientists but I think in our way we are doing something remarkable. I think we are somehow contributing to the decision-making in our region for our countries, just by keeping everything aside and focusing on one issue, that’s science. We do not fight when we deal with science. We only focus on physics, chemistry and biology and there is no space for other conflicts.’

Do you think it represents a model for cooperation?

‘Yes, because we always say that SESAME was modelled on CERN (the European Organization for Nuclear Research) (which succeeds) despite the conflicts in the past between the European countries. We take it as a role model. The war in Europe is over, but for us it’s not, so we have lots of challenges to keep going this way. We have to keep in mind all the struggling in our region parallel to constructing a facility like this.

‘We are scientists but we are still humans and we cannot close our eyes or ears to what’s happening around us but somehow we just decided to put these things aside and try to make something positive out of all this negativity.’

When you joined SESAME you were the only woman on staff. Is that still the case?

‘Yes. The facility declares the gender balance concept when they open the call for proposals or fellowships for training or users’ meetings or all the events related to SESAME. Women are strongly encouraged to apply. But the environment of a synchrotron is of a hard nature and not all the female scientists are able to cope with this hard work and it needs lots of compromises between their personal traditions and family life or whatever, so sometimes it’s difficult to cope with this.

‘We receive a good number of proposals for experiments (from women) and also they apply for training or short fellowships but so far it’s difficult maybe for many women scientists in the region to apply for a position at SESAME.’

‘SESAME is considered as a gate for all the female scientists in the Middle East and neighbouring regions, especially to those who are not able to travel abroad, facilitating their struggles and helping them in having an advanced scientific career.

‘The situation is getting better through the applications we receive, and we are all hopeful that as soon as possible, there will be more women scientists among SESAME staff.’

Tell us about how SESAME helps build scientific expertise in the region.

‘There are two parts to this question. The first one is about training – we go into that in two parallel ways, either we bring experts from other synchrotrons to train people at SESAME (or we) send SESAME staff to other synchrotrons to get special experience in a specific field. Also (we) arrange for training fellowships for any researcher from SESAME members to go abroad to a synchrotron to get trained and we recently opened a training fellowship for two months in any European synchrotron.

‘(There) is also the second point, the brain drain issue. We (Middle Eastern scientists) are all going abroad to have our PhDs or post-docs or even research positions abroad and many, many of us don’t come back because we don’t have these facilities. So we keep just flowing out of the region and this is why we see SESAME as a key for a brain drain reverse because it’s bringing us back.’

You’re originally from Egypt, you studied for your PhD in Italy and then you moved back to the Middle East to take up your position in Jordan in 2015. Are you an example of brain drain reversal in action?

‘I’m one of these people and there is another beamline scientist (who) was also in Italy and he also joined two years ago. Another beamline scientist was also in Switzerland and he came back to SESAME and it’s happening.’

Does SESAME give you hope beyond the science?

‘We don’t think of our villages or our nationality. We don’t have labels in there. Inside SESAME we are SESAME staff. I have attended SESAME users’ meetings for 12 years. In the beginning I saw people clustering in groups. If you saw the last users’ meeting last year, people were really mingling together and they were chatting and sitting together to discuss scientific projects even if their governments are in a really, really bad diplomatic situation.’