From the first discoveries of planets beyond our solar system in the 1990s, we now know of thousands of alien worlds, some of which could even be habitable to life as we know it. Now we need to detect more of these exoplanets and study them in detail, says astronomer Dr Michaël Gillon from the University of Liège in Belgium, who was involved in one of the most important exoplanet discoveries to date.

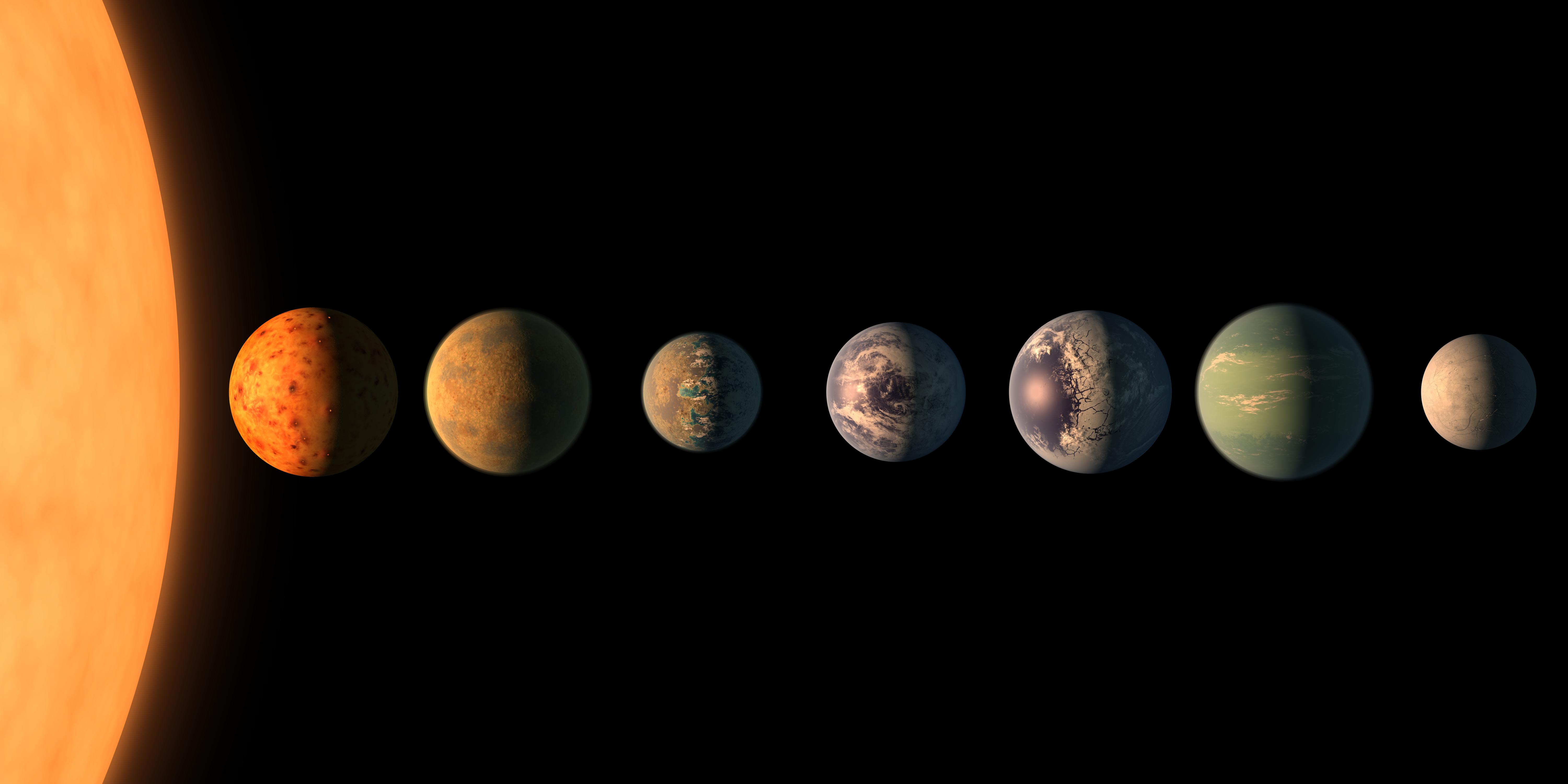

In 2017, his SPECULOOS project discovered seven Earth-sized planets around the TRAPPIST-1 system, one of the most intriguing planetary systems found so far – and now the hunt is on for more weird, wonderful, and even Earth-like worlds.

What were the goals of the SPECULOOS project?

‘The SPECULOOS project aimed to develop facilities composed of several robotic telescopes to search for exoplanets – planets orbiting around other stars – that transit very nearby (Earth) and around very tiny small stars (ultra-cool dwarfs), basically, the least massive kind of star. The goal was to search for planets that are potentially habitable and that are well-suited for detailed (atmospheric) characterisation by (NASA’s) upcoming James Webb Space Telescope (due to launch in 2021). Now we really want to move from exoplanet detection to exoplanet detailed study characterisation.

‘In 2017, (the project) achieved a wonderful result because it detected the famous TRAPPIST-1 system, which is composed of seven Earth-sized planets around one of the brightest and nearest SPECULOOS targets. This system is the best system so far for the study of temperate, potentially habitable planets with James Webb.’

How was the TRAPPIST-1 system detected?

‘In 2009, we installed a robotic telescope in Chile called TRAPPIST (Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope). The main goal was to do exoplanet transit photometry, so to confirm or search for transits of planets (by detecting the change in light intenstity when a planet passes in front of its star).

‘In 2016, we monitored (a system) very intensively. We had already announced the discovery of three planets in the system in spring 2016. We went on monitoring, also with (NASA’s) Spitzer telescope, and it resulted in the detection of seven planets instead of three.’

How many exoplanets have we found so far, and how many of those are potentially habitable?

‘Since the discovery of 51 Pegasi b in 1995, more than 4,000 exoplanets have been detected. Now we know for sure that most stars of our galaxy and in the universe harbour their own planetary system. But only a few dozen of these exoplanets (found) are potentially habitable. We want to detect more like the TRAPPIST-1 planets because they will present more opportunities to know more about the atmospheric and surface properties (of temperate rocky planets).’

What makes an exoplanet likely to be habitable?

‘Well, liquid water on the surface of a rocky planet. For this to be possible you need a solid surface, a rocky world, but you need an atmosphere that is dense enough to make pressure and temperature (possible) for liquid water. You (also) need a star that is not too harsh in terms of high energy radiation, that does not erode the atmosphere of the planet. The survival of an atmosphere is something that is dependent on the properties of the host star, too.’

What do we know about exoplanets so far?

‘We’ve learned from exoplanet discoveries that the diversity of planetary systems is very, very large. The only planets we knew of were in the Solar System, so we thought you had rocky small planets near a star, and giant planets rich in gas (far away). But it’s not at all the case. You can have planets that are rich in gas and migrate inwards. Sometimes you have a very compact system of planets like TRAPPIST-1. Sometimes you find planets in very eccentric orbits. You have planets around double stars, and planets that are free-floating in the interstellar void that have been ejected by young systems. So, the diversity of these mechanisms of planetary formation is really fascinating.’

So there are some free-floating exoplanets?

‘Yes, some have been detected by (gravitational) microlensing techniques. It has been inferred that there must be billions of them in the galaxy, ejected from young systems by interactions with other planets (or with a star). Fortunately, Earth is not among them.’

What are some of the biggest unanswered questions in exoplanet science?

‘I would say the frequency of really habitable planets is one of the main goals of the field now, to assess the frequency of planets with liquid water on the surface. Are planets around low mass stars habitable? Because these low mass stars tend to have high energy irradiation that is much harsher (than our Sun).

‘The habitability of planets around red dwarfs is one of the key topics now in the field. We are (also) still learning the details of the formation of planets, thanks to the diversity of planets we are detecting. We also want to learn more about super-Earths, which do not exist in our Solar System, planets between Earth and Neptune (in size).’

‘I would say the frequency of really habitable planets is one of the main goals of the field now: to assess the frequency of planets with liquid water on the surface.’

Dr Michaël Gillon, University of Liège, Belgium

What role will ESA’s upcoming CHEOPS telescope, launching on 17 December, play in our understanding of exoplanets?

‘It’s a very focused mission, which will do high-precision transit photometry, so measuring very precisely the brightness of transiting planets, to better determine the size of the planet. It’s a follow-up mission, and it will be able to do very detailed precise measurements on selected high-priority exoplanet targets. This is the first mission of its kind.’

Are there any other developments that could expand our understanding of exoplanets?

‘James Webb (telescope) will be able to make possible very detailed atmospheric characterisation of a large sample of (rocky planets around) low mass stars, and also giant planets (around Sun-like stars), using the transit method. But if we are interested in Earth-like planets in Earth-like orbits around Sun-like stars, we need to develop direct imaging techniques. These developments are ongoing, but it will take still decades to detect (and study) an Earth twin by direct imaging.’

The research in this article was funded by the EU’s European Research Council. If you liked this article, please consider sharing it on social media.

CHEOPS

On 17 December 2019, the European Space Agency is expected to launch its CHEOPS satellite to look in more detail at some of the exoplanets we’ve already found. The main aim is to better understand their structure in order to test theories of planet formation and evolution.

The on-board telescope, which weighs just 60kg, is designed to precisely measure each exoplanet’s radius and compare it to its estimated mass to understand what it is made of.

The data gathered should also help narrow down future observation targets by identifying planets with an atmosphere, which is necessary for a planet to harbour life.

Originally published on Horizon.