Mandated quotas are raising the number of women appointed to top company posts in Europe and sparking a cultural push for gender equality, but entrenched networks are getting in the way of achieving true boardroom diversity, according to researchers.

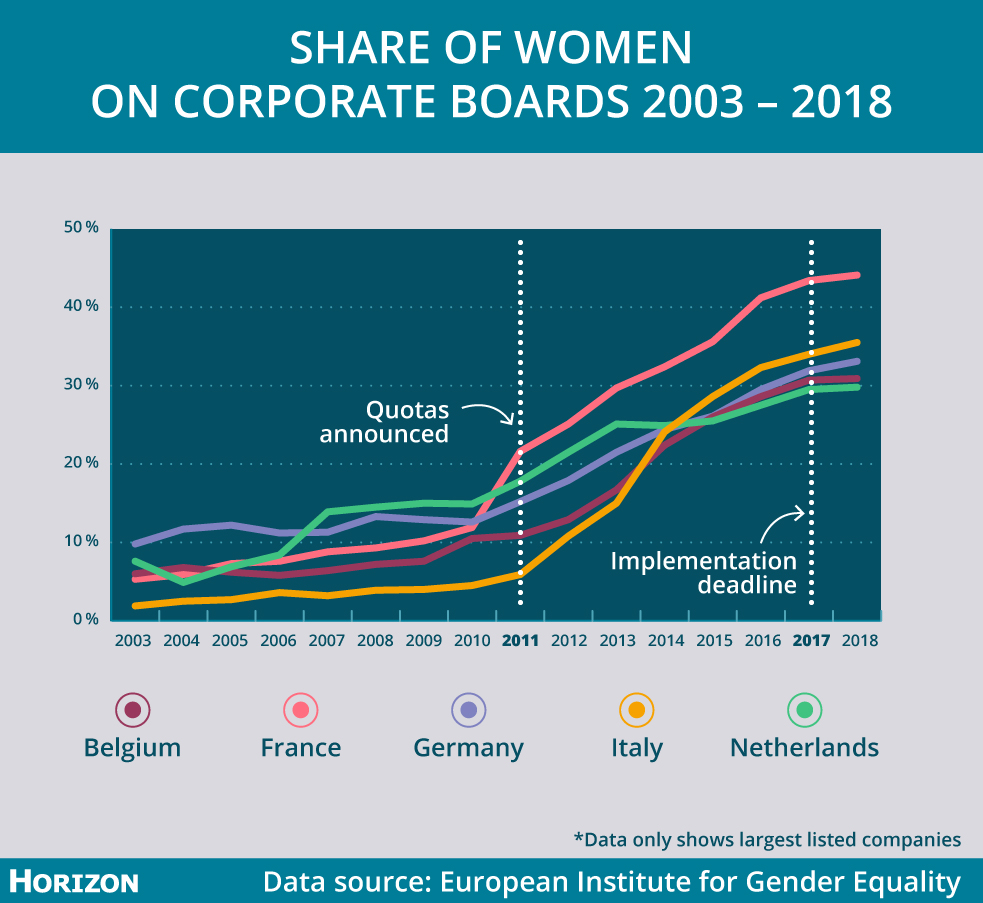

In recent years, a number of European countries have tried to tackle the underrepresentation of women on boards by introducing gender quotas of between 30% and 40%, with differing reach and levels of enforcement.

‘There are definitely more women on boards in countries that introduced legislation,’ said Dr Anja Kirsch, a professor at the School of Business and Economics at Freie Universität Berlin, Germany.

Norway was the first country to mandate a quota, passing a law 10 years ago, and firms risk dissolution if they don’t comply with the 40% target. Belgium, Italy and France have legislative quotas with penalties, including fines. Germany introduced a 30% quota without sanctions in 2015, while in the Netherlands companies must ‘comply or explain’ if they don’t hit the 30% target.

The European Commission has even proposed EU-wide legislation mandating that the under-represented sex make up 40% of companies’ non-executive directors (the average is 26% in the EU), which won’t pass unless Member States reach an agreement.

Getting more women into the top business ranks has increasingly become a topical issue in public and academic debate, says Dr Kirsch. For the past five years, she has been looking in detail at women’s access to boards in Germany, Europe’s largest economy where about half the workforce is female, as part of a project called BoardEquality.

480 women

Germany’s requirement since 2016 of 30% female-held board seats applies only to the supervisory board of publicly listed companies, the outside directors of the country’s two-tier system who appoint top management board members. What this means is that the quota only affects a small number of companies, about 100, and some 480 women, says Dr Kirsch.

Even so, it has increased the proportion of female supervisory members, Dr Kirsch points out. In 2015, women accounted for 26% of supervisory board directors and in 2018, 33%. The proportion of their male counterparts dropped from 73% to 69% in that period.

She believes that Germany’s quota should be expanded to include more types of companies, but is doubtful it could extend to management boards after the current law faced decades of resistance from society and companies.

The share of women on corporate boards rose since the quotas were implemented in five European countries. Image credit – Horizon

German legislation requires that the supervisory boards set targets for female management board directors that are no lower than the status quo within the company. Given that so many management boards are all-male, Dr Kirsch says the target is often zero.

However, she says that quotas establish responsibility and accountability within an organisation and, for her, the most striking outcome in Germany is that gender inequality within top management is now a live issue for the supervisory board members.

‘The women directors are making it an issue. They’re supporting other women,’ she said. She has now started work on a new project looking at how male colleagues can also support change.

For Dr Florence Villesèche, assistant professor at Copenhagen Business School in Denmark, quotas are not only working but, for now, they’re also the only means of achieving diversity. ‘In the sense that there are more women on boards – it’s not just a promise, a target or an aspiration – it actually happens,’ she said. ‘Quotas are the only tools that work in terms of sheer numbers.’

But they are a blunt instrument, according to Dr Villesèche. ‘Quotas are good, they’re effective, but they’re not enough – they are the tip of the iceberg, if you will. There is no automatic trickle-down effect. Policies and laws are, for now, mainly concentrated often on private firms.’

She says that there tends to be fearmongering that quotas promote women regardless of qualifications and that the discourse around merit – that people are hired to boards because they’re deserving – conceals the ‘invisible male quotas’. Dr Villesèche argues that quotas challenge such biases.

‘It is not an irrational thing to do, to implement quotas,’ she said. ‘It just forces firms to rethink their recruitment strategies, to question their bias, to reassess their own networks – so in which kind of circles do they scout candidates.’

Networks

Through a study called Womboardnet, which ended in 2017, Dr Villesèche examined the laws that get women into the boardroom but also the social phenomena – particularly networking – that hinders or enables qualified women to rise through the ranks. She analysed data to understand how board diversity has evolved in Switzerland and Denmark.

Change is still coming much too slowly, but it’s through such data that researchers can show firms there’s work to do, she says.

She found that accessing top levels is not just a question of gender but also the social connections forged through networking.

‘Quotas are the only tools that work in terms of sheer numbers.’

– Dr Florence Villesèche, Copenhagen Business School, Denmark

Dr Villesèche draws on the example of how when it comes to recruiting new board members from a few equally strong final candidates, unconscious biases come into play. These can include socially defined ideas about what someone can or can’t do according to gender or demographics, or the homophily principle where we prefer people who are like us.

According to Dr Villesèche, such preconceived ideas are linked to networking, which is crucial for visibility and advancing careers.

Dr Villesèche found that in Switzerland – now edging closer towards a quota law – where women are poorly represented in top company roles, that nationality and career paths tended to be more influential than gender. She also analysed networks discovering them to be gendered and nationality-orientated despite the country’s growing number of women and foreign directors. ‘Which means there is a continuous reproduction of the centres of power,’ she said.

For her, these findings suggest that policies and laws promoting diversity, rather than just focusing on broad stroke categories like gender, should consider the nuanced intersections with other demographic categories, such as nationality, social class and race.

The research in this article was funded by the EU.