Painstaking archaeological exploration is a familiar, often widely admired, method of unearthing history. Less celebrated, but also invaluable, is the piecing together of fragments of ancient languages and analysing how they changed over thousands of years.

Historical linguists have reconstructed a common ancestral tongue for most of the languages spoken today in Europe and South Asia. English, German, Greek, Hindi and Urdu – among others in the Indo-European family of languages – can all trace their origins to a single spoken one named Proto-Indo-European (PIE).

Linguistic ripples

The language is believed to have been spoken from roughly 4 500 BC to 2 500 BC. No written traces remain.

The people who spoke PIE probably lived in an area that is now eastern Ukraine. As groups broke away over the centuries to migrate across the continent, daughter languages stretched from Ireland to the Indian Ocean.

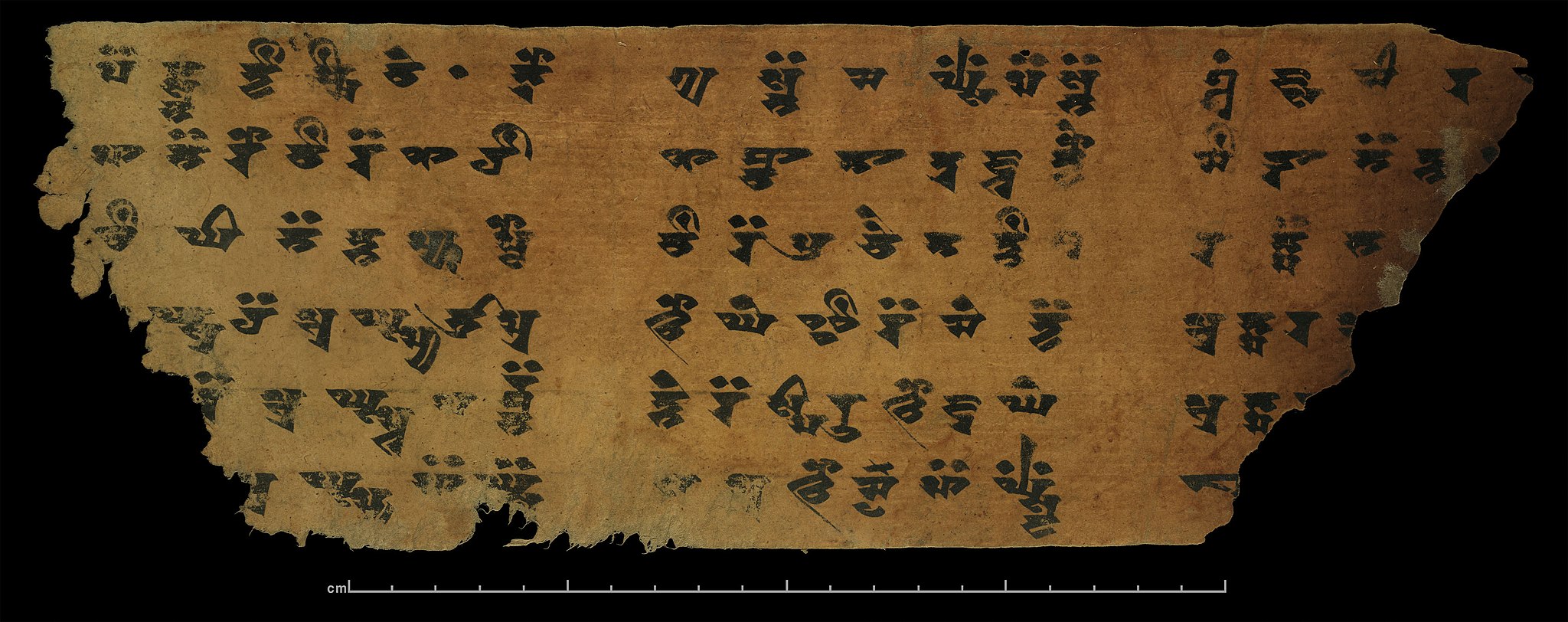

Yet the pattern included a notable exception: a now-extinct branch of the Indo-European language family made its way from Europe more than 4 000 kilometres eastward to end up at the Tarim Basin in northwest China.

Learning how and when these people, known as the Tocharians, undertook the odyssey are goals of an EU-funded research project.

‘It gives us a fascinating insight about how far people could migrate and what sort of risks and hardships they were actually prepared to expose themselves to,’ said Professor Michaël Peyrot of the Centre for Linguistics at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands.

Peyrot coordinates the European project, which is called TheTocharianTrek and is due to end in December 2023 after almost six years.

Tocharian trek

The research is helping to pin down where the Tocharians were located in the period between 3 500 BC, when they may have left their ancestral home, and their first written history in 400 AD.

In sum, the initiative is mapping the migration route from the PIE homeland all the way to China.

Through the journey, the Tocharians brought their dialect of PIE into contact with people speaking different languages. This influenced and changed the way the Tocharians spoke until finally their recorded languages evolved.

Archaeological and genetic evidence suggests that the Tocharians first moved to southern Siberia.

Peyrot and his research colleagues have sought to provide a linguistic assessment of this route. Their work reveals that, indeed, some of the quirkiest features of the language fit very well with tongues spoken in southern Siberia.

‘Languages preserve precious information about their prehistory through the effects of language contact,’ said Peyrot. ‘Observing the effects of language contact, such as borrowed words, enables us to draw conclusions about the proximity of the speakers of different languages and at which point in time the contact took place.’

As an example of a borrowed word, he cited a term for sword in a language strand known as Tocharian B: ‘‘kertte’’ was taken from ‘‘karta’’ in Old Iranian.

The research team has concluded that the Tocharians arrived in the Tarim Basin in around 1 000 BC – later than was previously thought.

As result, their window of influence in the Tarim Basin has narrowed and the Tocharians are being assigned a more muted role in the prehistory of the area than they have traditionally been given.

Instead, the project has found a strengthened role for Iranian languages and peoples in the area, especially Khotanese, its relative Tumshuqese and Niya Prakrit. All influenced Tocharian.

The project is also piecing together which languages left the PIE community first and when.

As their work enters its final phase, the researchers agree with the theory that the Tocharians may well have left the PIE family second and certainly well after the Anatolians, a group of ancient languages once spoken in present-day Turkey.

Weather terminology

Aside from offering insights into people’s interactions and movements, comparing vocabularies in languages descended from PIE provides a picture of the material world and day-to-day life at the time.

Much research has already been done on the family and social structure of the day, the livestock that people had and their tools in daily life.

But few studies have examined the shared vocabulary that these ancient peoples used when talking about something that is an equally popular topic of conversation today: the daily weather.

Dr Julia Sturm is combing through the lexica of ancient languages to pull out any words relating to weather and climate as part of another EU-funded project – IE CLIMATE – that she leads.

‘It’s important to have many perspectives on how we relate to climate and how we experience ourselves in the world,’ said Sturm, a postdoctoral fellow with the Roots of Europe Centre at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark.

The European project is due to wrap up in October 2023 after two years.

The work has involved scrutinising the written evidence of 10-plus Indo-European languages to find, for example, a word to convey cloud and then piecing together conclusions and timeframes about how one tongue influenced another.

Word atlas

The ultimate goal is to create an atlas that maps where the words were used and when. The completed atlas is due to be available on the university’s website beginning in late 2023.

While an archaeologist digs up physical objects at historical sites, Sturm combines formal linguistics and philology – the study of language in written and oral historical sources – to “excavate” words.

In both cases, the aim is to draw conclusions about the material world of the distant past.

Carried out in tandem with paleoclimatology, which is the study of climatic conditions in different periods of history, Sturm’s work gives new insights into the weather of the past and people’s attitudes towards it.

The persistence of metaphor is striking: how humans have personified elements in the natural world and related to them.

Greek, Latin and Vedic Sanskrit, for instance, all describe gods as wearing clouds, using the same verb to depict how people might don a shawl or a cape.

‘The more information we have about geography and time, the better,’ said Sturm. ‘In a world where the climate is changing so much and we are realising our role in the system, looking at the past brings an important new perspective.’

Research in this article was funded by the EU via the European Research Council (ERC) and the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions (MSCA). If you liked this article, please consider sharing it on social media.

More info